When I come home at night after classes and force myself to cook instead of resorting to the emergency boxed protein mac and cheese sitting in my kitchen cupboard, there is only one thing I want to do while eating: watch The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills. Television is dead, so I’ve reverted to watching reruns of my favorite quality shows (hello, Twin Peaks) and finding stimulation in the not-so-intimate lives of women who couldn’t be more different from me. Does it kill millions of neurons per minute? Possibly—but I make sure to keep a healthy surplus.

I can’t sugarcoat the nature of my enjoyment—it veers into schadenfreude at times.

It is voyeuristic—so much so that avid reality TV watchers have softened the meaning of the word, making it feel more casual and less perverse. With a cigarette dangling from her hand, Camille Grammer’s medium tells Kyle Richards that her husband will never emotionally fulfill her, and I laugh. They all try to attend soirées together despite a third of the group deeply resenting each other, and I can’t stop watching them attempt to feign tolerance. I live for it.

After a quick Google search, I learn that Taylor Armstrong’s abusive husband, Russell, committed suicide after the filming of the second season. I can’t stomach it. Should I be watching this? The birthday parties, the galas, the island excursions—they all resume at full extravagance, as if nothing happened. Up, down. In, out. It’s all so bizarre and slightly overwhelming that I’ve come to accept the rapid cycling of friendships and conflicts as the norm on a lonely planet called Los Angeles.

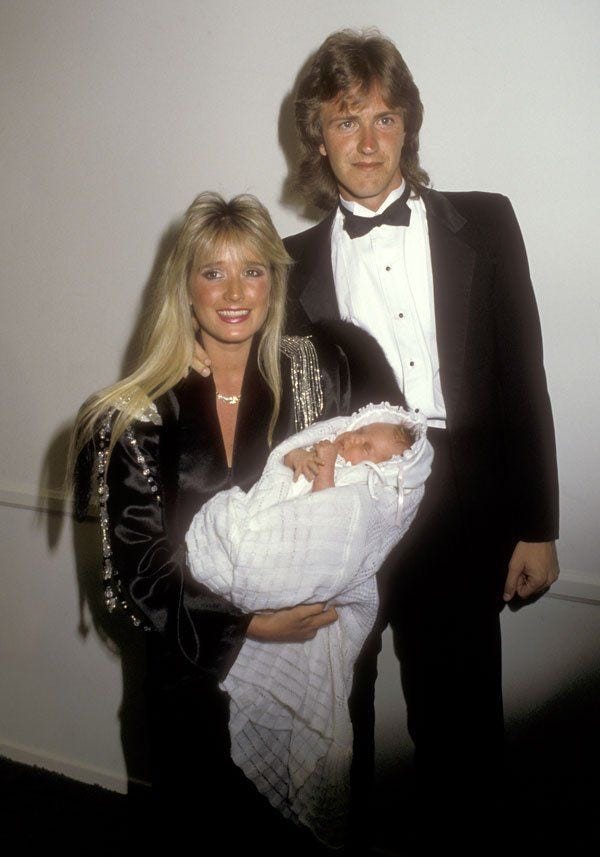

The cast member who has lingered in my thoughts the most—now a new addition to my list of topics I ruminate on while washing dishes—is Kim Richards. Nearly employed since birth, she has starred in countless television shows and movies spanning from the 1970s to the early 2000s. I recognized her from the original Escape to Witch Mountain and was floored to learn that she is Paris Hilton’s aunt. She has been married twice—first to a supermarket franchise heir, then to the son of a petroleum mogul—and by all accounts, she has hardly had a day to breathe outside of the public eye.

On RHOBH, Kim comes off as sweet, yet erratic and absent-minded. She also seems completely dependent on her very assertive sister, Kyle Richards. Her taglines in the opening credits include “People try to figure me out, but I’m one of a kind” and “Everyone loves a comeback story, especially starring me.” She is perpetually late to every event, never apologizes, and makes no effort to modulate her emotions in front of the crew. With her heavy-lidded gaze and regular trips to the powder room, she rarely seems sober.

Dropping her brisk, posh accent—one surely native to the Harrods aisles—Lisa Vanderpump mimics Kim’s slurred, valley-girl affect not once, but twice. When Kim suddenly turns cruel at a dinner or in some wannabe heiress’s living room, my first impulse is to resent her for the way she wields her privilege so carelessly. I suspect it's a class and culture clash.

Then, a week ago, I stumbled upon the 1985 film Tuff Turf. She’s captivating in it. This twenty-something Kim is the spitting image of the 1991 Totally Hair Barbie—golden, pin-straight hair cascading to her waist and a delicate, coral-colored mouth. Everyone wants to look into her dark, slightly downturned eyes and dance with her. As she reverts to a coy half smile around James Spader’s character, I see a woman with a summery, all-American beauty whose charm stems from her elusiveness. I want to celebrate her for all the small, lovely quirks I lack. No, I don’t pity her loss of youth (she’s still gorgeous) or feel more empathetic toward her because of her beauty. I pity the fact that she moves the same in a scripted movie as she does on The Real Housewives. I sense that she isn’t acting when she looks down pensively or erupts in bubbly laughter. This is the same girl whose addiction, thirty years later, will amount to yet another storyline in the tangled jumble of a reality TV show. It feels tragic that my first instinct is to see tragedy.

I don’t want to figure Kim out. I could never claim to understand her history because, from personal experience, I know that crucial intricacies are always left out on paper. The idea of conducting a deep dive into any potential abuse she may have faced makes me uneasy.

The only thing I’m sure of is that Hollywood takes pleasure in watching beautiful women crumble—because it has decided their appeal should exist only within the confines of a corporation. There’s even money to be made from the wreckage that occurs outside of this space.

Most people, having allowed their natural jealousy to grow unchecked, can’t stand the idea of someone—particularly a woman—who possesses every superficially attractive trait: a career, physical beauty, a magnetic personality, etc. A studio audience and vulturous directors and producers who raise a young girl will always end up producing the ideal woman for consumption. Industry heads never have to worry about working with someone too self-aware to preserve their soul—because their project child actress is a patchwork of attributes she would have never thought twice about without intervention. These “stars” are like jigsaw puzzles—carefully arranged to form the right image, but upon closer inspection, none of the pieces truly fit together. From a distance, though, it all looks and sells just fine.

Can you ever truly leave to find yourself if you were never given a choice in who you are?

When I think about what I’ve seen of Kim, I’m reminded of The Truman Show—not because I see her as a fictional character (I don’t), but because of the essence of her existence on screen. Unlike Truman, Kim has always been aware of when she’s being filmed. But does the way she understands behavior in front of the camera align with how we see it? I’m hesitant to say yes. In the film, Truman doesn’t grow up with the expectations of a public figure in mind because he wasn’t aware that he was one then. Kim did—but somewhere along the line, it made no difference. She cries, lashes out, and indulges in her vices—things most people engage in behind closed doors—as if the set and the landscape of her life fused years ago. My observation is that, for her, they are indistinguishable. Like Truman Burbank, Kim Richards has been making a profit for someone through on-screen appearances since before she had reason to understand it.

But Kim isn’t a jester who reappears every other episode—she’s a real, deeply flawed woman who is devoted to her children.

By pushing someone like Kim Richards (or any willing participant, for that matter) toward reality TV show fame, we are breathlessly waiting for them to crash and burn, popcorn in hand. Since leaving the show, Kim almost seems to exist solely within the domain of the latest article detailing her holiday plans or stint in rehab. The pressing thing to note is that there are countless Kim Richardses on our screens and feeds. Some claim to have been rehabilitated through intervention, others never recovered, and most insist that childhood stardom left them unscathed. Still, everyone knows that the entertainment industry preys on malleable, innocent minds, only to discard them once they've fully formed. That kind of treatment sticks with you, no matter how much time passes or how far you wander from where you came.

I hope Kim is doing well with her loved ones. And if she is, more than anything, I hope that I—along with every other viewer out there—never find out.